This paper discusses the various liquor policies adopted by prominent Indian states and their direct and indirect impact on the Economy as a whole and the consumers in particular. The paper emphasises the adoption of a new liquor policy by the Delhi and Punjab governments and what factors led to the success or failure of this policy. It portrays the incompetence of some Indian states in achieving a beneficial approach instead, giving rise to political upheaval. The Indian states have reconsidered the liquor policy multiple times, considering its massive impact on the country’s GDP. Being a heavy liquor consumer, minor policy changes can disrupt the whole dynamic, and such challenges must be mitigated through appropriate steps and procedures.

Literature Review

Seventh Schedule. As a result, the state controlling the manufacturing of alcohol or alcohol production differs from state to state. The State Government collects excise duty on alcohol, alcoholic preparations, and narcotic substances, known as “State Excise” duty. Consumer prices are typically increased due to excise taxes, which lowers consumer demand for taxed goods. Consumers’ price elasticity of demand determines the extent of the drop and who will be most impacted by prices. Revenue generation has historically motivated and often continues to inspire these taxes. There is a wealth of data on how taxes and prices affect the demand for alcoholic beverages and tobacco products. Since the excise policies have impacted its consumers and the GDP, it is essential to analyse the shortcomings and pros of such policies deeply. Indian states follow state-wise policy according to their social and economic situation, and their framework sometimes leads to a negative impact and raises social and political controversies.

About Liquor policy in India

Alcohol is a subject under the State List of the Indian Constitution. Except for Gujarat and Bihar, which have implemented prohibition, liquor contributes significantly to the exchequer of all states and UTs. In general, states impose excise taxes on the manufacture and sale of liquor. Some states, such as Tamil Nadu, levy VAT (value-added tax).

States also levy additional fees for imported foreign liquor, transportation, and label and brand registration. A few governments, like Uttar Pradesh, have placed a “special levy on liquor” to collect cash for specific reasons, such as stray cattle care.

According to a report published by the RBI last year, state excise duty on alcohol contributes to approximately 10-15% of the Own Tax Revenue of most states. The state excise duty on liquor is the second or third most significant contribution to the State’s Tax revenue category, with sales tax (now GST) being the largest. This is why states have always sought booze to be exempt from GST.

Why is liquor sale important for Indian states?

Except for Gujarat and Bihar, which have strict prohibitions, liquor contributes significantly to the exchequer of all states and union territories. In general, states impose excise taxes on the manufacture and sale of liquor. Some states, such as Tamil Nadu, levy VAT (value-added tax). States also levy additional fees for imported foreign liquor, transportation, and label and brand registration. A few governments, like Uttar Pradesh, have imposed a “special levy on liquor” to raise cash for specific objectives, such as stray cattle care.

According to a report issued in September by the Reserve Bank of India (‘State Finances: A Study of Budgets for 2019-20’), state excise duty on alcohol accounts for approximately 10-15% of Own Tax Revenue in the majority of states. State excise fees on booze are the second or third most significant contribution of State Own Tax revenue, with sales tax (now GST) being the largest. This is why states have always sought liquor t be exempt from GST.

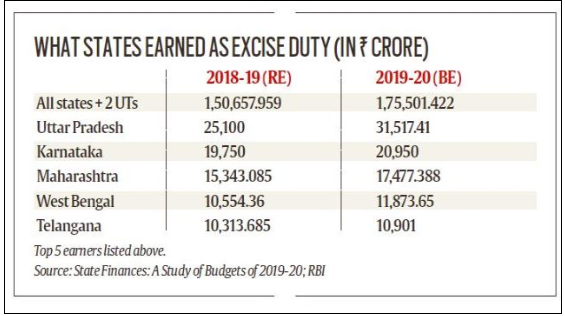

According to the RBI report, the 29 states and the UTs of Delhi and Puducherry budgeted a total of Rs 1,75,501.42 crore in state excise on liquor for 2019-20. It was 16% more than the Rs 1,50,657.95 crore collected in 2018-19. In 2018-19, states collected roughly Rs 12,500 crore per month on average from liquor excise, which increased to about Rs 15,000 crore per month in 2019-20 and was likely to cross Rs 15,000 crore per month in the current fiscal year.

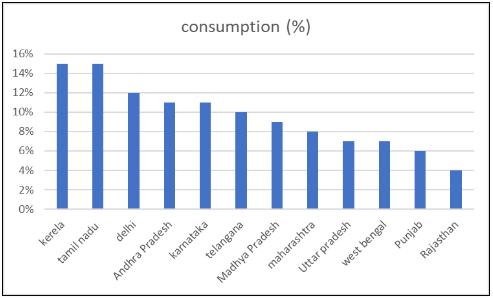

States accounting for 75% of liquor consumption in India for Indian made foreign liquor and beer:

Delhi’s old liquor policy

Delhi has 864 liquor stores, 475 managed by the four government agencies and 389 by private operators. Under this regime, Delhi observed 21 dry days, although, under the new rule, liquor stores were only closed for three days. There was no minimum area requirement for opening a liquor store in Delhi, and no discounts were granted.

About Delhi’s excise policy for the years 2021-22

Delhi is one of India’s most visited cities and 28th in the world ranking. Because of the significant footfall, excise revenue is one of Delhi’s essential sources of income. The current excise regime in Delhi is highly complicated, and the liquor trade is archaic. According to the Delhi government, the new Excise Policy for Delhi has the potential to significantly increase revenue generation and provide a decent level of customer experience to build the national capital. On November 16, 2021, the Delhi Excise Policy 2021-22 went into effect. It revolutionized the way liquor was sold in the city by removing the government from the business and allowing only private operators to operate liquor stores, with other changes.

The Excise Department’s primary role is to regulate, control, and monitor the possession, import, export, transport, sale, and consumption of liquor and other intoxicants. The ability of the state to control and regulate liquor trade is introduced in entry 8, list II-state list of the seventh schedule of the Indian constitution. According to List II-State List entry 51, states have the authority to collect excise duties and anti-subsidy duties on liquor for human use while taking economic and social issues into account. The statutory authorities are discharged for this purpose under the Delhi Excise Act, 2009.

Delhi’s new liquor policy, first announced in 2020, has lofty ambitions. To begin with, the strategy was intended to crack down on the capital’s booze mafias, which aligned with the Aam Aadmi Party’s anti-corruption agenda.

Domains of Delhi excise policy for the year 2021-22

- Walk-in Experience- According to the Excise Policy for 2021-22, every liquor shop will provide a walk-in experience to customers, with several brands to pick from and an entire standard selection and sale process completed within the property.

- There will be no crowds outside the liquor vends; retail vendors with air conditioners will have glass doors. Customers will not be permitted to crowd outside the vending machine and purchase via the counter.

- Draught Beers at Bars- Under the Delhi Excise Policy, consumers can fill their bottles with freshly brewed beer from any of the city’s microbreweries.

- Bars will be open until 3 a.m.- Except for those who have been granted a license to operate round-the-clock service liquor, bars, hotels, restaurants, and clubs are permitted to remain open until 3 a.m.

- Super Premium Vendors will be required to stock at least 50 imported liquor brands, including wine brands.

- Special Excise Adhesive Labels- The Delhi Government intends to use special inspection teams and a state-of-the-art lab to combat tax evasion, retail vendor conduct, and counterfeit liquor.

Under the new excise policy, Delhi would be divided into 32 zones, each with 27 liquor vends and a minimum of five ultra-premium liquor sellers spread throughout the city, with a carpeted space of 2,500 square feet. The strategy would see the Delhi government completely withdraw from the liquor market, enabling private operators to fill the void. Following a bidding process established by Delhi’s Deputy Chief Minister Manish Sisodia, the Excise Department gave licenses to 849 commercial sellers under this new policy. The strategy also promised several significant changes to how liquor was purchased and used in the capital, such as decreasing the drinking age from 25 to 21 and cutting the number of dry days to three.

Issues with the liquor policy

- The Excise Department permitted the opening of more vending machines in “conforming zones” without the authorization of the appropriate authority. It was also seen that several licensees were having difficulty opening their businesses in these so-called ‘non-conforming’ regions.

- Most of the 849 private sellers soon found themselves under a severe financial strain, as hefty licensing fees, fierce competition, and price gouging rendered the industry unviable for the smaller firms.

- Due to the hefty upfront expenses paid to the government under the new system and lesser revenue due to fierce competition and discounts, an increasing number of licensees began to abandon the industry, leaving at least nine of the 32 zones vacant.

- Vinod Giri, director general of the Confederation of Indian Alcoholic Beverage Companies (CIABC), said, “In a fundamental misconstruct, the size of zones was too big. We repeatedly raised the matter of keeping zone sizes small to reduce the financial stakes of the bidders (and increase viability) and to prevent monopolies. But none of that was taken into consideration. We also suggested more simplicity and flexibility in operational issues such as license ownership changes, but to no avail,”

- The number of shops dropped from 639 in May to 464 in July, eight months into the remodelled system. The original proposal called for 849 private retail liquor vends. However, the shops never reached that number, and customers in some areas were forced to travel to other neighbourhoods to find their preferred brand, particularly those seeking more costly products.

- According to the Aam Aadmi Party, the leading cause of the issues was that former LG Anil Baijal amended a policy clause at the last minute, resulting in hundreds of vends not opening in sites where they would have been set up. The secondary reason was that the Policy was authorized at the macro level but not allowed to be fully implemented at the micro level, resulting in many license holders leaving.

The controversy

The scandal began when Delhi Chief Secretary Naresh Kumar submitted a report highlighting suspected anomalies to Lieutenant Governor VK Saxena and Chief Minister Kejriwal. According to the article sent by the chief secretary, Delhi Deputy Chief Minister Manish Sisodia, who leads the excise department, was accused of changing the excise policy without the L-G’s approval.

According to multiple media reports, these revisions included a ₹ 144.36 crore waiver on the surrendered license price due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It further claimed that liquor licensees were given undue advantages by modifying foreign liquor tariffs and eliminating the import pass charge of Rs 50 per case of beer. According to sources, this resulted in a revenue loss for the state exchequer.

L-G VK Saxena recommended a CBI investigation into alleged rule violations and procedural problems in implementing the excise policy on July 22, 2022. He also instructed the Delhi chief secretary to investigate the role of excise department personnel in the alleged anomalies and a charge of ‘cartelization’ in the retail liquor license bidding process.

On July 28, 2022, Deputy Chief Minister Manish Sisodia, who also holds the excise portfolio, asked the department to “revert” to the former excise policy for a six-month term until a new approach is in place.

The Excise Policy 2021-22, slated to expire on July 31, was extended for one month, as were current liquor licenses. However, Delhi will revert to the former excise regime for six months from September 1.

Liquor policy implementation in Punjab

On June 7, the Punjab Cabinet adopted the state’s new excise policy for 2022-23, which is estimated to produce $9,647.85 crore in revenue. The decision was made at a meeting in Chandigarh presided over by Chief Minister Bhagwant Mann. According to the official statement, The policy’s goal is to collect 9,647.85 crores in 2022-23, and it will be in effect for nine months, from July 1, 2022, to March 31, 2023.

TIMELINE:

The Punjab Government developed the excise policy for the fiscal year 2021-2022, generating roughly Rs 6,158 crore in income. Then the Punjab Government renewed and extended the excise policy for the fiscal year 2021-2022 for three months, from April 1, 2022, to June 30, 2022, in March 2022.

The government adopted a new excise policy for 2022-2023 in June 2022, for nine months spanning July 1, 2022, to March 31, 2023. The revenue generated during the specified period is estimated to be Rs 9,647.85 crore.

The new strategy aims to retain a tight grip on liquor smuggling from neighbouring states through aggressive enforcement, including the use of technology. The Cabinet also approved allocating two special battalions of police to the Excise Department, in addition to the existing force, to keep an effective monitor over excise duty pilferage, according to the statement.

The programme calls for leveraging the actual potential of the liquor sector by allocating 177 groups through a free, fair, and transparent e-tendering process. According to the policy, the strategy includes provisions for new distillery and brewery licenses to promote capital investment and increase job capacity in the state.

With the quota now open, Indian-Made Foreign Liquor (IMFL) and beer prices will be somewhat lower beginning July 1, with some brands’ pricing matching those in Chandigarh. The rates will be 10 to 15 per cent lower than in Haryana. Beer prices will range between ₹ 120 and ₹ 130 per bottle, ₹ 120- 150 per bottle in Chandigarh. Beer costs roughly ₹ 180- 200 per bottle in Punjab right now.

Similarly, the most popular IMFL brand will cost Rs 400 in Punjab versus ₹ 510 in Chandigarh. The bottle is currently priced at Rs 700 in Punjab.

The Punjab government wants to increase excise collection by 40% on the assumption that liquor smuggling from Chandigarh and Haryana will halt when liquor prices decline.

Issues with Punjab’s policy

Akash Enterprises and other wholesale and retail vendors challenged the regulation in the Punjab and Haryana High Court. They claimed it was an attempt to monopolize the liquor trade. The petitioners argued that the government had published a corrigendum increasing the maximum number of retail groups that can be given to an organization from three to five, furthering the government’s objective of concentrating the liquor market in the hands of a few resourceful bidders.

The price reduction has given cheers to consumers. The tariffs on booze in the wholesale sector have been reduced by 25-60%. Also, no quotas have been set in the new policy for selling Indian-made foreign liquor (IMFL) and beer, which means vendors can sell as much liquor as they want. But this comes with many problems for the people of the state. According to the latest report by the Chandigarh-based Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, alcohol is the most often misused substance in Punjab, with more than two million people abusing it, followed by tobacco, which is consumed by more than 1.5 million people (PGIMER). Opioids are used by 1.7 lakh people, followed by cannabis and sedative-inhalant stimulants. The latter is primarily a subset of abused pharmacological or prescription medicines. According to the PGIMER’s State of Punjab Household Survey and statewide NCD STEPs Survey, the estimated number of overall substance use in Punjab is 15.4 per cent. Considering these facts, the policy harms the lives of people and their families.

Other states

Kerala

BEVCO (Kerala State Beverages (Manufacturing & Marketing) Corporation Ltd) is a wholly owned public sector corporation founded under the Civil Supplies Department in Kerala. A Judicial Commission highly endorsed the company, which was founded in 1984. The primary goal of BEVCO was to provide consumers with high-quality booze at reasonable costs while preventing overuse. This was to be accomplished by creating an appropriate method to combat the illegal distribution of counterfeit booze and eliminate the intermediary, duties, and taxes. It was established to take over wholesale distribution of liquor gradually and, eventually, to set up distilleries to obtain spirit and arrange blending, bottling, sealing, and distribution of arrack and sale of IMFL throughout the state of Kerala. BEVCO currently controls all retail sales of Indian Made Foreign Liquor (IMFL) and beer in the state. Throughout Kerala, it has 23 Warehouses (FL-9 Shops) and 270 Retail Outlets (FL-1 Shops). Liquor sales generated Rs 11,743.99 crore in revenue during the last fiscal year, which is only 5.28% less than the previous year. After subtracting operational expenditures, manufacturer bills, and other costs spent by the state, liquor sales brought in Rs 12,398 crore to the state exchequer in 2019-20.

IMPACT

In 2001, the Corporation was entrusted with the bulk of retail shops to safeguard consumers from rising alcoholism. Since 2007, the Kerala government has tried to tighten its excise policy, reportedly for public health grounds, to restrict the supply of liquor in the State.

Initially, the State attempted to amend the policy by awarding new bar licenses only to hotels with three-star or above ratings from the Central Government’s Ministry of Tourism. In 2011, these restrictions were revised once more. Any hotel with fewer than four stars was prohibited from obtaining a license to sell alcoholic beverages on their grounds.

During Oommen Chandy’s Congress administration, Kerala implemented prohibition in stages in 2014. The Chandy government’s liquor policy required Kerala bars to renew their licenses yearly. This regulation resulted in the closure of 418 bars. At the time, the bar owners’ lobby opposed the measure. Bar owners allegedly bribed many ministers to secure liquor licenses. In 2017, the left-wing government overturned the state liquor policy and phased in prohibition, predicting an annual loss of Rs 8,000 crore in excise revenue due to ban. The government also proposed deaddiction centres in all district headquarters to address alcoholism while raising the license fee and the age for drinking to disincentivize supply and consumption.

In 2018, the Kerala government increased the excise duty on liquor by 0.5% to 3.5% for 100 days during Onam, generating more than Rs 11,000 crore for the state exchequer. The government currently levies a 202% sales tax on booze, which costs BEVCO less than $400 per case (12 bottles). Every year, the sale of drinks produces Rs 2,500 crore in taxes for Kerala. The alcohol sales from BEVCO shops generated the highest revenue of Rs 14,508 crores in the fiscal year 2018-19. Moreover, despite the pandemic, BEVCO’s revenue in FY 2020-21 was Rs. 11,743.99 crores.

During the Covid-19 outbreak, the Kerala Government decided to open liquor outlets in the state with tokens to purchase liquor, to be issued through a mobile app that allowed users to choose the nearest location and raise additional revenues while also limiting the spread of the infection. Taxes on wine and beer were increased by 10%, with an additional 10% fee on liquor bottles under 600 millilitres. All other types of alcohol were taxed at 35%. According to State Finance Minister Thomas Isaac, the liquor tax increase generated an estimated Rs 2,000 crore in additional revenue for Kerala.

Policy Failure

Promoting expensive brands may harm Kerala’s 63% of total alcohol drinkers who prefer inexpensive spirits. Brandy drinkers may have fewer options as costly food, primarily whiskey, takes up the shelves. Due to the economic crisis brought on by the COVID-19 epidemic, most alcohol consumers still find it difficult to purchase even regular booze. However, the absence of “cheap things” at State-run stores may drive many of them to hunt for “fake” alternatives. It has been suggested that fake IMFL travels extensively from Delhi, Mumbai, and Goa to the State. Additionally, the spirit is also used in many areas of the State to create fake alcohol

Andhra Pradesh

Andhra Pradesh State Beverages Corporation Limited (APSBCL) was founded in 1986 as an unlisted public business. It was reincorporated in 2015 and is now a State government-owned enterprise. The state passed the (Regulation of Wholesale Trade and Distribution and Retail Trade in Indian Liquor, Foreign Liquor, Wine, and Beer) Act in 1993 to regulate the wholesale trade and distribution of Indian liquor, foreign liquor, wine, and beer as well as the retail trade. Under Article 47 of the Indian Constitution, the law was enacted as a preliminary to prohibit the consumption of intoxicating liquors. The AP administration imposed a booze embargo in 1994. However, it was later repealed in 1997. In 2019, the state government announced the New Excise Policy, under which AP State Beverages Corporation Ltd took over retail liquor outlets from private operators beginning in October 2019.

IMPACT

In October 2015, the excise duty on low-end alcohol brands was reduced. This primarily aimed to raise state revenue by expanding booze sales. This increased the price of premium brands by 25-100 per cent while decreasing the cost of low-end booze by 5-10 per cent. This action, however, drew criticism because of the increase in consumption. Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy stated in May 2019 that he would not seek votes if he failed to deliver on his promise of a total liquor ban in the state by 2024. Following that, the AP government assumed control of the state’s liquor business to “curb liquor sales,” reducing 1,446 retail liquor outlets from 4,380 to 2,934.

Not only did the government take over liquor sales, but they also declared an Additional Retail Excise Tax (ARET) on alcohol sales beginning October 1, 2019. Additional taxes were charged on the price of Indian Made Foreign Liquor, Foreign Liquor, Beer, Wine, and ready-to-drink variations at a fixed rate per bottle to improve the state’s finances. Customers have to pay an additional Rs 250 for 2000ml booze bottles. Beer prices increased by Rs 10 for 330ml and 2,000 for 50,000ml with new levies in 2019. Ready-to-drink options were available for an extra Rs 20. In May 2020, the Andhra Pradesh Special Enforcement Bureau (SEB) was founded to tackle illegal liquor. It also detained 43,976 people in 33,754 between May and August.

The AP government terminated all liquor store permits and closed 43,000 belt shops in October 2020, with the maximum possession limit of booze lowered to three bottles of any size. Despite the AP government’s considerable efforts to restrict alcohol throughout time, it has only increased the illicit liquor trade and smuggling of liquor from other states, with many individuals ending up in jail due to booze-related offences in 2020.

However, officials found that consumption of Indian-Made Foreign Liquor was down 37% in May 2020, while beer consumption was down 70%. Despite the decline in consumption, the government generated approximately Rs 17,600 crore from liquor sales in the fiscal year 2020-21. A similar amount was earned in FY 2019-20 after enhancing the tax rates by more than 125% in two years.

Policy Failure

The cost of premium liquor brands makes smuggling goods illegally across the border easier. Despite several enforcement measures, including establishing the Special Enforcement Bureau (SEB), there is still widespread alcohol smuggling. The most important reason for this increase in inter-state smuggling is the increased liquor prices in Andhra Pradesh due to an upward revision of rates compared to the prevailing liquor prices in the neighbouring states, especially in Telangana and Karnataka. In the aftermath of the lockdown, there were tragic occurrences of persons dying after consuming sanitisers and methyl alcoholic preparations, in addition to an upsurge in the smuggling of alcohol into Andhra. As stated, the government would reduce the number of liquor stores by 20% per year but instead decided to open more bars.

Tamil Nadu

The state auctioned off a liquor store and bar licenses for retail vending. However, this resulted in the development of cartels and a loss of revenue for the state. To combat this, the government implemented a lottery system in FY2001-02, in which potential bidders bid for stores grouped by income. However, the lot system could not avoid cartelization because bidders later withdrew in favour of others. The government amended the Tamil Nadu Prohibition Act, 1937, in October 2003, becoming TASMAC the state’s exclusive retail vendor of alcohol. TASMAC’s state-imposed monopoly on selling Indian Made Foreign Liquor (IMFL) aims to end cartelization. By 2004, the business had closed or taken over all private liquor stores. TASMAC has complete control over liquor distribution in Tamil Nadu. Because of the possibility for profit, subsequent governments attempted to strengthen TASMAC’s hold on booze sales. The AIADMK directed that all hotels and pubs obtain liquor through TASMAC.

IMPACT

Tamil Nadu generates more than two-thirds of its revenue on its own (2018-19 actuals). Alcohol taxes account for around 25% of the state’s total revenue (2018-19 actuals). In addition, revenue collection in Tamil Nadu fell by 5% on average between 2011 and 2017. Along with this, the GST regime has done little to help, increasing Tamil Nadu’s reliance on central transfers. This is where the TASMAC has proven useful. TASMAC produces money through selling annual licenses to run bars in its retail stores, in addition to tax revenue (excise tax and sales tax). The state’s consistent revenue growth can be attributed to periodic increases in retail pricing and rising alcohol consumption. Tamil Nadu was able to make Rs 31,000 Crores in revenue during the fiscal year 2018-19 through the TASMAC.

TASMAC’s massive income was essential for succeeding state governments. The funds have frequently been utilized to entice voters, ranging from free colour televisions by the DMK to free fans, mixers, and grinders by the AIADMK. According to reports, the state promotes local brands by artificially restricting supply. A new entry must either build its distillery or cooperate with an existing company. Rockford Reserve’s maker, Modi Illva India, has launched the whisky in 18 states but has yet to enter Tamil Nadu for this reason. That could also explain why beverage behemoths like Pernod Ricard have avoided the state.

Policy Failure

Despite the extent of its activities and financial success, TASMAC’s 25,000 or more employees feel mistreated, and their pay is far less than that of the typical government worker. This has led to the development of a corrupt and criminal underworld that everyone is aware of, but no one wants to confront. It is not surprising that fraud and corruption are common in the outlets, given the low pay and poor working conditions. In addition to overcharging customers, issuing incorrect bills, and diluting drinks, the sales staff also engages in other unlawful acts. Selling “cuttings,” slang for alcohol sold by the peg rather than in sealed bottles, is a typical side hustle. Several incidences when the Directorate of Vigilance and Anti-Corruption wing has confiscated sizable sums of undeclared cash, ranging from Rs. 60,000 to Rs. 3 lakh, from TASMAC shops throughout the State can be used to estimate the level of corruption in these outlets. In one instance, TASMAC investigators discovered a startling Rs. 3 crore shortfall from the outlet’s four-month earnings while examining a Thoothukudi location.

Recommendations

Tax policies in accordance with the health of individuals:

States must develop an optimal differential taxing scheme to provide a monetary incentive for people to switch from high-concentration to low-concentration alcohol, causing a portion of the population to favour beer or wine over hard liquor. Mild alcoholic beverages with less than 5% ABV can be taxed under the Goods and Services Tax (GST). Wines manufactured from local grapes can be tax exempted. Fruit wines (subject to low ABV) can promote moderation, enhance the local economy, and preserve local culture. A progressive taxation system creatively exploits the difference in alcohol content between hard liquors and low-concentration alcohols (and the related differential public health consequences) to calibrate the price signal.

Model Proposition by the Central government:

The central government can play a crucial role in the excise policy by introducing a uniform set of suggestions that the states can adopt. This can include a more regulated policy with people’s participation in what we support.

📌Analysis of Bills and Acts

📌 Summary of Reports from Government Agencies

📌 Analysis of Election Manifestos