Revisiting the Kanyashree Prakalpa of West Bengal

This paper aims to analyse the Kanyashree Prakalpa policy of the West Bengal government that was launched in 2013 on the 14th of August. The study’s objective is to focus on the policy’s objectives and implementation aims. There is a detailed critical analysis of the policy along with a description of the positive outcomes of the policy. Previous survey data and statistical findings have been incorporated into this paper and the study of the research done by the previously published works on this policy. Recommendations have been provided at the end of the paper with suitable examples. This paper’s main objective is to highlight the Kanyashree Prakalpa as, despite being an award-winning scheme of a state government, not much study has been done on this policy.

Introduction

West Bengal has a rich history of revolutionaries and women’s rights liberation movements. Raja Rammohan Roy fought against the evil discriminatory practices of child marriage and emphasized its abolition during British rule. In 1929, the marriage age for females increased to 14 and 18 for men. However, after independence and with the advent of the new era of independent India, there has been a continuous degradation in the field of female education in the state of west Bengal. The state saw a rapid increase in the rate of child marriages and a deterioration in the number of adolescent female students dropping out. With the political regime transition in 2011, there was a new ray of hope for development in the state. The Kanyashree Prakalpa was an initiative introduced at a time when West Bengal had the highest number of child marriages, and young girls were victims of this unlawful practice in the state. According to government reports, in 2011, when the country was experiencing an average of 3.7 per cent of child marriages, West Bengal was at 7.8 per cent. The new chief minister of the state, Smt. Mamata Banerjee initiated the Kanyashree scheme for the disadvantaged female sections of society in 2013. Through this scheme, the young women in the state aspire to get state-funded assistance in their education and a preventive measure against child marriage. The following sections of the paper explain a detailed analysis of the scheme.

Keywords: Policy, women, child marriage, education, dropouts, cash transfer

1. Rational behind the need of such a policy

1.1 Illegal Underage Marriages

Under the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act of 2006, the legal marriage age in India is 18 for girls and 21 for boys. Even though this Act has been in effect for several years, child marriage continues to be practised in West Bengal. According to government reports, from 2007-08, the state ranked fifth in the country regarding child marriage prevalence, with nearly every second girl (54.7%) married as a child bride. Despite being more prevalent in rural areas, more than a quarter of Kolkata girls marry before adulthood, even in non-slum areas.

The West Bengal districts with the highest rates of child marriage also have the highest rates of human trafficking. Child marriage and dropout from school are inextricably linked. Girls’ school attendance in West Bengal falls from 85% in the age group 6-10 years to 33% in the age group 15-17 years (NFHS III, 2005-06). Enrolment and completion of the elementary school in India have increased since the implementation of free and universal elementary education; however, the transition from elementary to secondary school remains a concern. Secondary education is not free, and many impoverished parents, unable to see the economic benefit of investing in their daughters’ education, marry them off at this age in the mistaken belief that it will provide them with a better future.

Figure 1: Comparative percentage of underage marriage with other states(2011)

Source: https://factly.in/child-marriages-in-india-reasons-state-wise-analysis-child-abuse/

Following the passage of the PCMA in 2006, the Department of Women’s Development, Social Welfare, and Child Development (DWD) launched anti-child marriage campaigns, spreading the message of prevention and endorsing the laws and its penal provisions for adults who aid and abet child marriage. However, it soon became clear that legal prohibition and social messaging are largely ineffective in combating child marriage. For one thing, India’s plethora of formal and religious laws complicates the question of what age is appropriate for girls to marry. Second, because the practise is rooted in time-honoured tradition and is justified from a patriarchal standpoint as necessary for protecting girls from the evils of society, eradicating it necessitates tangible social change agents capable of transforming victims.

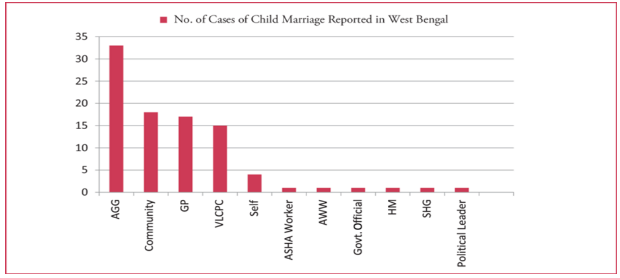

Figure 2: Child marriages reported by various agencies in West Bengal (2011)

Source: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Information-on-Child-Marriages-West-Bengal_fig1_308513916

1.2 Adolescent Dropouts from Schools

West Bengal had a problematic number of dropouts from educational institutions among the adolescent females and males. There was a steep rise in the early 2000s in this numbers. It was quite surprising that neighbouring states which were rather less developed than West Bengal had a lesser number of dropouts among the adolescent boys and girls.

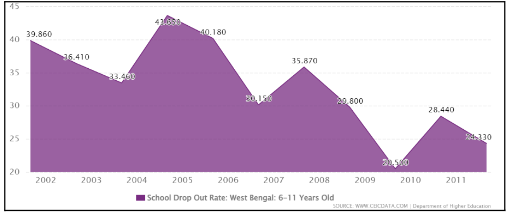

Figure 3: The trend in school dropouts prior the KP in West Bengal

However, surprisingly the number in this share was more for the boys than the girls. In the rural areas, the tendency to send children as underage labour and to assist the parents in the domestic aids are the main causes behind dropouts from schools. The underage marriage is another reason and that is the grave reason why young girls are forced to exit schooling. Many superstitious beliefs are also at a fault behind these occurrences. Menstruating women are generally avoided to enter in the public sphere and thus compelled to leave schools. Many times, stereotypical environment hinders the advancement of the women towards attaining higher education. The minimum ability to read and write sometimes is sufficient for them and they dropout unable to cope up with their household chores along with the studies. Men are needed for financial assistance and thus are deported to the cities by their families at a young age. Along with this lack of faculty, good teachers and the negligence of governmental schooling are the other causes behind the school dropouts.

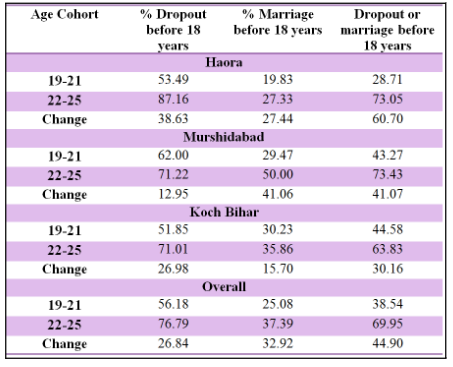

Table 1: District wise distribution of dropouts of women

(Year 2011)

Source: https://www.theigc.org/blog/reducing-age-marriage-school-dropout-west-bengal/

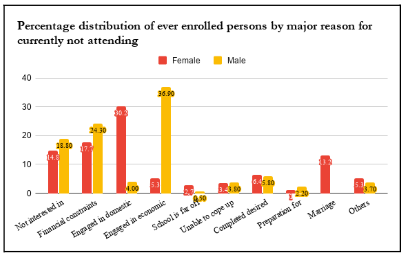

Figure 4: Reasons for Dropouts all over India

Source: https://www.turnthebus.org/blog/school-dropouts-in-india-the-cause-and

2. Layout of the scheme

The Kanya Shree Prakalpa was the West Bengal Government’s flagship programme launched in 2013. Its main aim is to bring about a reduction in the number of underage marriages and the development of female education for disadvantaged women in the state. This programme has a two-tier conditional cash transfer facility for girls belonging to the age group between 13 to 18 and whose annual family income is less than 1.2 lakh. This is, however, not applicable for the girls who are especially abled or have special needs. Girls residing in orphanages and J.J. homes are also excluded from this condition. The local governing bodies must submit a certification before claiming that the Scheme is beneficial.

The Scheme 3 components within its layout are KP1, KP2, and KP3. The first component (KP1) is the provision of an annual grant of around ₹750 to the girls enrolled in any educational institution and in classes ranging from standards VIII to XII. Under the KP2 component, there is a provision of a grant of ₹25,000 to girls 18 years of age who have an education qualification, any kind of vocational training, sports or any other kind of training till that age. This is a huge boost to the self-esteem of the girls as well as ensures minimum corruption in the system. Forms for such applications are provided to the respective schools, and the school officials provide all the other procedures regarding the bank account initiation. There is a prevalence of the usage of the E- Portal where the candidates can enter all their details, inquire about all their queries, and clear their doubts. Schools, mass media, celebrity endorsements, “Kanya Shree Melas” (fairs) and street theatre are used to raise awareness. The initiative was promoted through ASHA publications distributed by the Department of Health and Family Welfare at Department of Mass Education libraries and advertising distributed by the Department of Consumer Affairs. This, along with a strong political will, has guaranteed that this system is well known. This initiative has attracted tremendous grassroots support and media attention since its start. UNICEF India funds the programme, and participants have helped to establish and organise the state’s communication strategy. The U.N. agency also helped to create the MIS (monitoring and information system).

Their assistance has provided significant technical support to the government’s overall K.P. endeavour. The third component of the scheme KP3 gives ₹ 2500/- per month to an unmarried female student with 45% in her undergraduate studies to pursue her postgraduate science courses. Under the same conditions, the sum for the social sciences, humanities and Commerce streams is ₹2000/- each month. Since 2017, the yearly family income limit has been eliminated to broaden the Scheme’s scope. The project’s distinguishing traits are its simplicity of design, ease of accessibility, focused communication strategy, concurrent execution, and emphasis on enhancing the girls’ financial, social, and self-worth.

Image 1: The basic layout of the scheme on the official website

Source: https://wbkanyashree.gov.in/kp_scheme.php

3. Aims and objectives of the Scheme

According to the West Bengal government’s initiative, this policy aims at emancipating all the girls in the state. It aims to provide an annual amount of 120000 to all the young women attending any educational or vocational training courses. Kanyashree Prakalpa seeks to improve the status and well-being of girls, particularly those from socioeconomically disadvantaged families, through Conditional Cash Transfers by incentivising them to stay in school for more extended periods and complete secondary or higher secondary education or equivalent in technical or vocational streams, giving them a better footing in both the economic and social spheres. (Government 2013)

Legalising the age of marriage until 18 years, thereby reducing the dangers of pre-mature pregnancies, linked with dangers of infant and maternal mortality, as well as the chronic risks of malnutrition. It was also decided that the Scheme should provide more than just monetary assistance; it should be a financial inclusion and empowerment tool. The Scheme’s benefits are thus paid directly to bank accounts in the girls’ names, leaving the decision of how to spend the money in their hands. The Scheme also improves girls’ social power and self-esteem through a targeted behaviour change communication strategy to reinforce the positive impact of increased education and delayed marriages. The communication strategy includes adolescent-friendly approaches such as events, competitions, and Kanyashree clubs, as well as the endorsement of strong women figures as role models to promote social and psychological empowerment. (Government 2013)

4. Analysis of the policy at the grassroot level

4.1 Positive outcomes of the scheme

Image 2: Mamata Banerjee celebrating the Kanyashree Divas on 14th August 2021

The scheme was launched on March 8, 2013. It has been discovered that over the last five years, the number of girls dropping out has decreased, and in the final Board examinations, girls outnumber boys in the 10th and 12th grades in various districts. Child marriage is now a rarity in West Bengal. Early marriage, premature motherhood-related health risks, and maternal and child mortality have decreased. According to the Annual State of Education Report (ASER)-2020, the school dropout rate in West Bengal fell from 3.3% to 1.5%, while it increased from 4% to 5.5% nationally. West Bengal leads the nation in the decline of school dropout rates between 2018 and 2020. School dropout rates in rural areas are from various age groups, but it appears to be the highest in the 15–16-year-old age group, where the decline is 4.8%. Girls aged 7 to 16 have taken the lead in school enrolment. The Pandemic’s Impact However, the unforeseen and unfortunate pandemic caused by COVID-19 and the prolonged closure of educational institutions has posed a severe threat to the regular studies of girl children. Because they are confined to their homes, they must bear the brunt of household chores. Due to a lack of a smartphone at home or a reliable internet service provider, the digital divide has deprived them of e-learning, at least in the form of a WhatsApp group, particularly in rural areas. They are denied the nutritional guarantee of a cooked mid-day meal programme and the weekly iron and folic acid supplement tablets provided by schools across the country to combat anaemia. In terms of quality education, such prolonged absenteeism equates to ‘out-of-school children.’ Furthermore, the Bank frequently disrupts stipend disbursement to beneficiaries due to KYC issues that they are unable to address due to home confinement.

According to a study in Howrah, Murshidabad, and Koch Bihar, the proportion of girls not pressured into underage marriage has increased by 5.17, 4.04, and 2.67 percentage points, respectively. (Dutta 2020) It’s also encouraging to see that the proportion of girls who resisted such pressure grew. Similarly, all districts have decreased the proportion of women who did not resist pressure to discontinue education. One concern about this cash transfer was that it would be used as a dowry in marriages and that the practice of dowry would be encouraged. The KP2 money was used to fund the higher education of 57.89% of the girls in Howrah and 43.48% in Koch Bihar. In Murshidabad, where many girls did not pursue higher education, 55.56% saved their money rather than using it for marriage. Thus, while some of the girls did use the KP2 money for the wedding, possibly as dowry, they did not constitute the majority, and the funds aided the majority of them in their higher education, allowing them to meet the target. (Dutta 2020)

Image 3: Dance drama performed by school girls

Though the KP appears to have had a significant impact, and the programme appears to have been successful in reducing adolescent dropouts and child marriage to a large extent, a significant proportion of girls continue to drop out or marry before the age of 18, and thus fall outside of the KP net. In Murshidabad, 26% of girls between the ages of 14 and 18 are either dropped out or married, compared to 23% in Howrah and Koch Bihar, respectively. This is due to a lack of encouragement for boys’ education, and as a result, the parents of young women are fearful of the consequences of their daughters’ higher education, which may cause difficulties in finding suitable grooms.

Table 2: Utilisation of the KP money by the recipients

| Howrah | Murshidabad | Koch Bihar | Total | |

| Higher education | 57.89 | 22.22 | 43.48 | 45.10 |

| Marriage | 15.79 | 11.11 | 17.39 | 15.69 |

| Business | 0.00 | 11.11 | 0.00 | 1.96 |

| Savings | 26.32 | 55.56 | 26.09 | 31.37 |

| Others | 0.00 | 0.00 | 13.04 | 5.88 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

Source: Arijita Dutta and Anindita Sen, “Kanyashree Prakalpa in West Bengal, India: Justification and evaluation” International Growth centre. September 2020

4.2 Awards and international recognitions

| 1. West Bengal Chief Ministers Award for Empowerment of Girls, 2014 |

| 2. Manthan Award for Digital Inclusion for Development (South Asia and Asia Pacific) 2014 under the category E-Women and Empowerment. |

| 3. National E-governance Award 2014 – 2015 awarded by the Department of Administrative Reforms and Public Grievances, Government of India. |

| 4. Skoch Award and Order of Merit 2015 for Smart Governance |

| 5. CSI-Nihilent Award, 2014-15 |

| 6. United Nations WSIS Prize 2016 Champion in e-Government Category (WSIS Action Line C7) |

| 7. Finalist in GEM-Tech Awards 2016 organized by ITU and UN Women |

| 8. 1st Place Winner in UNPSA Award 2017 |

| 9. The “Girls Summit organized by DFID and UNICEF (London, July 2014) |

| 10. Consultation on “Child Marriage and Teenage Pregnancies” organized Tata Institute of Social Sciences (Delhi, March 2015). |

| 11. Consultation on “Empowerment of Adolescent Girls” organized by the World Bank (Ranchi, May 2015). |

| 12. National Workshop on “Conditional Cash Transfers for Children: Experiences of States in India” organized by NITI Aayog, India (Delhi, December 2015). |

| 13. Trafficking in Persons (TIP) Enclave organized by U. S. Consulate & Shakti Vahini (Siliguri, February 2016). |

Image 4: The chief minister of West Bengal receiving the United Nations public service award at Hague for Kanyashree Prakalpa

4.3 Limitations of the scheme

Policies are planned carefully to benefit the citizens of the state. However, a lot of socio-economic limitations are connoted when we talk about any policy. The following are significant limitations for the Kanyashree Prakalpa: Due to the patriarchal stereotyping of society, most women who belong to the underprivileged sections of society do not consider the option of securing a higher degree as a possibility. Domestic chores have always been a barrier in the field of female education. Most women imagine themselves getting married by the age of 25 and having their own children. Very few aspire to be unmarried and earn at the age of 25. The least number of women are interested in securing higher education degrees. However, a fair number of KP recipient girls above 18 aspire to get married and earn. Another issue with the socio-economic limitations can be the continuous increase in the number of self-initiated marriages, which were mostly below the legal age of marriage. This indicates the development of the liberating mindsets of women, but not in the correct direction. Pre-marital sex and having relationships with local boys are still taboo in many parts of the country. This creates a lot of restraints amongst young women and men. This, in hindsight, results in eloping and marrying against the families’ wishes. Unless a strong awareness campaign and sex education are offered to these girls, it might lead to an overall rise in underage marriage. It was found that over the age cohorts, there has been a sustained increase in self-age marriage, along with a fall in an under-age marriages arranged by parents.

5. Comparative study of the Other States’ models similar to Kanyashree

Over the last two decades, India has implemented a slew of programmes aimed at improving girls’ overall living conditions. They have targeted various social evils such as female foeticide/infanticide, which results in a low sex ratio, a lack of empowerment and health care facilities for women, a lack of education for girls, and child marriage. Many schemes, such as the Balika Samridhhi Yojana in Gujarat, the Bhagyalakshmi in Karnataka, the Kanya Jagriti Jyoti Scheme in Punjab, and the Beti Hai Anmol in Haryana, aim to improve the education of girls. (Dutta 2020) These programmes assist girls from low-income families at various levels of education, attempting to alleviate the burden. More effective are conditional cash transfer schemes for girls’ education, such as the Bangaru Thali in Andhra Pradesh, Ladli in Delhi in 2008, and Vidyalakkshmi in Gujarat in 2003. While the Bangaru Thali provides yearly transfers to girls upon enrollment and completion of each standard, the Vidyalakshmi pays ₹20,000 to a girl upon completion of class eight and then stops at the age when girls are most vulnerable to early marriage. Girls in Delhi can file a maturity claim after passing the 10th standard if they are eighteen or have passed the 12th standard under the Ladli scheme. While all of these programmes promote girl child education, they are all contingent on the girl completing each stage of the programme.

Kanyashree Prakalpa is not a debutant regarding conditional cash transfer policies. One of the first CCTs to do so was the Apni Beti Apni Dhan (ABAD) scheme launched in Haryana in 1994. (Dutta 2020) In ABAD, bonds of ₹2500 were distributed at the time of birth of a girl child and could be redeemed when she was eighteen conditionals upon remaining unmarried and passing class 10. (Dutta 2020) ABAD was similar to KP but left out the condition of continuing girls’ education till 18 years. Girls who dropped out of school after class 10 had a far higher chance of getting married at underage. In ABAD, the parents had to register at the time of birth of the girl child, whereas, in KP, the girls registered themselves at the age of 13. The Ladli Lakshmi Yojana was initiated in 2007 in Madhya Pradesh and subsequently implemented in other states like Jharkhand. Goa is another CCT. A girl receives a lump sum of more than ₹1 lakh at the age of twenty one, provided that she does not get married before eighteen and completes her secondary education. The emphasis on the girl’s completing her education (instead of just continuing till eighteen as in KP) acts as a deterrent. The Kanyashree Prakalpa is a unique scheme covering the education cost for teenage girls in India. After the age of eighteen, the girl receives ₹1 lakh per annum for continuing her studies if she is not married before that. The smaller portions, albeit little, are supposed to give the teenage girl a sense of self-empowerment and improve her aspirations to reach eighteen years. (Dutta 2020)

6. Recognising the Flaws and the problematics of the scheme

There have been a lot of governmental-level difficulties with the scheme. District Project Management Units were functional in each district. DPMU in North 24 Parganas has established the most structured and transparent system of establishing annual targets for the enrolment of girls. Most of the beneficiaries have heard about the Kanyashree Prakalpa from the school and reported seeing some television advertisements. There was considerable advocacy by the district and block administration with schools and colleges in an effort to ensure knowledge of and uptake in the scheme. Headteachers note that in the first year of Kanyashree’s implementation, the scheme generated discussions amongst teachers, parents and students – both formal and informal – around child marriage. In the initial year, all schools held camps to distribute forms and help students fill them out after a thorough orientation. (government 2015) Though the application forms are scrutinised religiously, there has been no evidence of a systematic physical verification process of the applications made. Some schools mentioned that they kept the receipts as they felt that the girls would lose them. Although the government has reduced the number of documents to be scanned and uploaded, even those implementers with high-speed connections report that some e-operations on the Kanyashree portal take far longer than on other websites (Dutta, 2020). A critical gap in the system that can affect the scheme’s credibility is the absence of a universal mechanism to track the transfer of the benefit to the recipient. Under the current system, the bank transfers funds to the appropriate beneficiary after the DPMU sends a batch of sanctioned applicants to the district bank. As this information is not part of the E-Portal, such information is cumbersome to collate at the district level, and there is no systematic tabulation of how many applicants have received their benefits. In North 24 Parganas, generally, the forms are uploaded within 1-2 days if the same is done by the teaching / non-teaching staff of the school. However, it takes longer if the uploading has to be done at the Block level. The inability of the e-portal to reconcile sanctioned applications with actual bank transfers was considered a major limitation. (Government 2013) Several stakeholders also suggested that user interfaces, although simple, suggested that users be allowed a more extensive combination of filtering criteria when generating reports. It was observed that the IFSC code of the beneficiaries automatically changed in case of application renewals. Technical issues need to be resolved quickly, and two-way communication between the e-portal’s implementers and district and block implementers must also be maintained on technical issues. A systematic grievance redressal mechanism is absent. Several applicants or their families report having to run between block offices, district offices and banks to get their issues resolved. An analysis of complaints would provide information on systemic problems that hinder smooth implementation.

Image 4: Self-defence training

7. Recommendations for a more inclusive and active scheme layout

The Kanyashree Prakalpa is aimed at ensuring underprivileged girls stay in school. According to the state government reports, there are nearly 57 lakh beneficiaries of this scheme. Experts and activists say there are concerns about its ability to curb trafficking. Kanyashree is an umbrella scheme that includes several other anti-trafficking initiatives. In September 2018, the West Bengal government launched the Swayangsiddha scheme to combat human trafficking. Complaint boxes have been installed in schools as part of the scheme so that girls can report any stalking or harassment they or their friends have experienced. “These are different sectors of government working together for the same goal of empowering the girl child and preventing child marriage and trafficking,” said Sanghamitra Ghosh, secretary of the State’s Women and Child Development department. Syawangsiddha is a West Bengal police scheme that is not as widespread as Kanyashree.” (Singh 2019)

The Kanyashree Prakalpa has received a huge response and has been hailed nationally and internationally as a scheme capable of bringing about social change in West Bengal’s marriage practises and women’s educational attainment. The impact of this conditional cash transfer on underage marriage and adolescent dropout among girls was estimated in this report. It was discovered that there had been a significant improvement in these two parameters in the four years since the program’s implementation. The impact of KP2 on child marriage has declined over the last four years. One possible reason for this decline may be the fall in the real value of the amount given at eighteen. Another could be the rise in self-initiated underage marriage, nullifying the impact of the programme in reducing social pressure among parents to get their daughters married off early. The Kanyashree Prakalpa, with an eye on empowering adolescent girls, has indeed made them financially literate and reduced pressure from families regarding discontinuing education and marrying early (Dutta, 2020). Without adequate awareness about the evils of early marriage and the need for education, such policies cannot hope to have an impact in the long run. Awareness campaigns among girls, generating leaders who can motivate their friends and giving them sex education at this crucial junction of life is something the government should surely consider. In the district of Murshidabad, the district administration developed the idea of “Kanyashree Yodhhas” (Singh, 2019). Similar awareness strategies and programmes might be charted to make this scheme more effective and sustainable. Even after providing cash transfers to encourage girls to study, the dropout rate in rural West Bengal is quite high. Students either cannot cope with their studies and drop out, or they must take private tuitions, which they frequently cannot afford and must drop out (According to the NSSO 71ST Round reports). A major educational reform must be implemented in order to improve not only the educational infrastructure but also the quality of education. The Kanyashree Prakalpa is intended for students whose annual family income is less than Rs. 1,20,000. This scheme, however, has been almost equally utilised by students whose families report a monthly expenditure in excess of the $10,000 stipulated by the scheme. Such ill strategies violate the principles of social justice. The girls’ parents involved in the formal sector would not be able to procure the scheme’s advantages even after fulfiling the income ceiling conditions. The Kanyashree Prakalpa has emerged as quite a successful scheme that can go a long way in ushering in social change if supplemented with awareness campaigns and educational reforms. A major educational reform must be undertaken where the educational infrastructure and quality of education must be improved to retain the students. (Dutta 2020)

A Way forward

The Kanyashree Prakalpa was a shocking need of the hour, related to the state of West Bengal and its issue of underage marriage and adolescent dropout for girls during the early 2000s and the next decade. The programme moved away from a simple scholarship for girls or life-cycle investments for girl children whenever she was born. The other states were offering that. Instead it took the shape of a unique conditional cash transfer scheme with dual targets. Conditional Cash Transfer schemes in various forms and levels have been widely introduced in several African and Latin American countries to augment enrolment and retention rates while bridging the gender gap. The main aim behind such CCTs is to counter the propensity to under-invest in most of the human development indicators in developing countries, especially related to women and girls. Literature suggests that the link between education and marriage timing is not isolated; instead, they are conditioned jointly by the broader cultural and socioeconomic context. High shares of out-of-school girls coupled with early marriage have severe implications on their empowerment, health care and skill development, which were identified to be strongly present in West Bengal. With a more transparent and active framework, the policy can gain more robust bases in the state and form an impact on the states through its outreach and success.

Bibliography

Arijita Dutta and Anindita Sen, “Kanyashree Prakalpa in West Bengal, India: Justification and evaluation” International Growth centre. September 2020

“Rapid Assessment Knyashree prakalpa” West Bengal government report. April 2015, Accessed on 18th august 2022 https://wbkanyashree.gov.in/readwrite/publications/000113.pdf

Arijita Dutta and Anindita Sen, “West Bengal’s Successful Kanyashree Prakalpa Programme Needs More Push from State and Beneficiaries”, Economic and political weekly, April 2018

Shiv Sahay Singh, “Kanyashree stipends are no shield against trafficking”, The Hindu, March 2019, Accessed on 20th August 2022 https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/kanyashree-stipends-are-no-shield-against-trafficking/article26420349.ece

Tushar Kanti Ghara and Krishna Roy, “Impact of Kanyashree Prakalpa – Districtwise Analysis”, IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS), July 2017

“Impact of Kanyashree: School dropout rate among girls comes down in Bengal”, All India Trinamool congress, August 2015, Accessed on 21st August https://aitcofficial.org/aitc/impact-of-kanyashree-school-dropout-rate-among-girls-comes-down-in-bengal/

“The trouble with the cash transfer scheme for girls’ education”, The Telegraph, March 2019, Accessed on 18th August https://www.telegraphindia.com/opinion/the-trouble-with-kanyashree-prakalpa-the-cash-transfer-scheme-for-girls-education/cid/1686355

Ahashanul Karim, Koyel Palit and Debjani Guha, “Empowerment of girls and Kanyashree Prakalpa: The Present Scenario”, International journal of multidisciplinary and educational research, May 2021.

📌Analysis of Bills and Acts

📌 Summary of Reports from Government Agencies

📌 Analysis of Election Manifestos