There are a variety of social, environmental, economic and psychological parameters leading to development of delinquent tendencies among children. Research studies and analysis have found that children growing up in a hostile domestic environment, under ineffective parenting, under conditions of substance abuse and psychiatric disorder are more prone to delinquency. According to data collected by National Crime Records Bureau(NCRB) in 2018, a high percentage of juvenile crimes involved children who were either illiterate, or educated up to primary level only, or lived with their guardians or were homeless.

The purpose behind any juvenile law is not to punish a juvenile but is to safeguard him against the evils of crime society. Another aspect of Juvenile law is to reform and rehabilitate juveniles so as to evolve themselves as crime-free human beings. Also, through punitive measures, it serves to act as a deterrent to habitual young offenders.

TABLE 2: BACKGROUND OF JUVENILES IN CONFLICT WITH LAW IN 2018(Source:NCRB)

Illiterate

|

3,610

|

Upto Primary educated

|

10,666

|

Above Primary to above Higher Secondary Educated

|

23,980

|

Living with Parent

|

32,433

|

Living with guardians

|

3,432

|

Homeless

|

2,391

|

History of Juvenile Justice System:

- The Apprentice Act was introduced in 1850 under which children convicted and belonging to the age group 10-18 years were to be reformed and rehabilitated through apprenticeship in a trade, i.e.,vocational training.

- IPC came 10 years later and sec 82(5) of the IPC provided immunity to all children below 7 years of age based on the principle of doli incapax. The latin term basically means ‘incapable of crime’. It is considered that children below 7 years are not mentally developed enough to judge the consequences of their actions and are therefore unable to differentiate between right and wrong. As an extension of the same, sec 83(6) also provided selective immunity to children in the age group seven to twelve years.

- Under the Reformatory Schools Act, 1876, Reformatory schools were established and children accused of crime were to be held there until they were able to find employment.

- The Children Act, 1920 was implemented in Madras based on the recommendations of the Indian Jail Committee appointed in 1919. It was followed by the Bengal Act in 1922 and the Bombay Act in 1924. These three Acts were extensively amended between 1948 and 1959.

- The first landmark legislation in this matter after independence came through a central enactment, The Children Act, 1960. It was a law meant only for the Union Territories and passed with the objective to provide care, protection, maintenance, training, education and rehabilitation of delinquent or neglected children.

- The Children (Amendment) Act was passed in 1978 to remove some inherent lacunas in the above mentioned Act,

- Although the need for a uniform legislation regarding juvenile justice for the whole country had been voiced loudly , including in the Parliament, it could not be enacted because the subject matter of such a legislation fell in the State List of the Indian Constitution. Even the Supreme Court was in favour of such a law.

- To bring the operations of the juvenile justice system in the country in conformity with the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice (Beijing Rules, 1985), Parliament exercised its power under Article 253 of the Constitution read with Entry 14 of the Union List to make laws for the whole of India to fulfill International obligations.

- The Juvenile Justice Bill, 1986 was introduced in the Lok Sabha on 22nd August, 1986, becoming the first law to be effective uniformly over the entire territory of India.

- In 1992, the government of India ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, thus making it imperative to enact a law that conformed to the standards of the Convention. Therefore, the JJA, 1986 was repealed and the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2000 was enacted.

Salient features of the Juvenile Justice Act, 1986:

- Defined a child or juvenile as a boy below the age of 16 years or a girl below the age of 18years.

- Children were categorized as delinquent juveniles and neglected juveniles. Both these categories of children were kept in an observation home together awaiting inquiry/trial. Juvenile Welfare Board was constituted to look after neglected juveniles whereas the Juvenile courts were the adjudicating authority for delinquent juveniles. The neglected juveniles were then sent to Juvenile Home and the delinquent juveniles to the Special Home.

Salient features of the Juvenile Justice(Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2000:

- It defined a child or juvenile as a boy or girl below the age of 18 years. It focussed on both children in conflict with law, and children in need of care and protection.

- Juvenile Justice Board(JJB) was to be constituted in each district to deal with matters relating to children in conflict with law. It was to comprise a first class judicial magistrate and two other social workers as members, at least one of whom should have been a woman.

- Child Welfare Committees(CWC) were also to be constituted in each district to handle children in need of care and protection. It was to comprise of a chairperson and four other members, at least one of whom should be a woman,

- It expanded the category of children in need of care and protection to include victims of armed conflict, natural calamity, civil commotion, child who is found vulnerable and likely to be inducted into drug abuse.

- The Act also offered more legal protection for the child in conflict with law. It prescribed detention to be resorted to as the last option, disqualification of past records and privacy to be maintained.The law outlined four options of restoration for children in children’s homes and special homes which include adoption, foster care, sponsorship and after care.

- The Act provided for the establishment of various kinds of institutions such as Children’s Home for the reception of children in need of care and protection and Special Homes for the reception of children in conflict with law. Observation Homes were meant for the temporary reception of children during the pendency of any inquiry. After-care Organizations were meant for the purpose of taking care of children after they had been discharged from Children’s Home or Special Homes.

- Under this Act, no minor could be convicted for a period of more than 3 years or tried in an adult court or sent to an adult jail, under any circumstance.

Reasons for amending JJA,2000:

- A massive public outrage following the Nirbhaya gang-rape case of 2012 took place, in which one of the accused was a juvenile aged 17. As per the then existing law, the maximum punishment that could be handed was a 3 year stay at an observation home even when the crime fell in the category of a heinous crime.

- There were implementation issues and procedural delays in adoption of the previous JJA law.

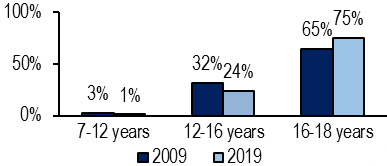

- According to the National Crime Records Bureau(NCRB) data, the crimes committed by minors, especially in the 16-18 age group, were on the rise and hence necessitated a more stringent law.

- The 2000 Act also did not have provisions for the reporting of abandoned or lost children to the appropriate authorities, in order to ensure their protection and care.

Juveniles arrested by age group

Sources: Crime in India, 2009-2019, National Crime Records Bureau; PRS.

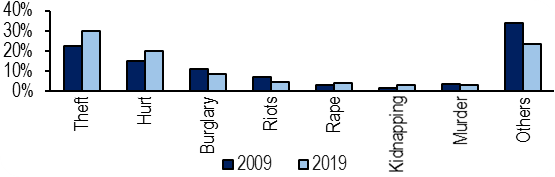

Types of crimes committed by juveniles (under IPC)

Note: Others include attempt to murder, fraud, blackmailing, dacoity, rash driving.

Sources: Crime in India, 2009-2019, National Crime Records Bureau; PRS.

Juvenile Justice Act, 2015:

- It brought about a change in the nomenclature and redefined ‘Child’ as a person being below the age of 18 years, requiring care and protection. Likewise, ‘Juvenile’ was used for persons below the age of 18 years and in conflict with law, i.e., having committed a crime. The Act also defined orphaned, surrendered and abandoned children.

- It clearly defined three types of offences:

Heinous Offences– such offences for which there is a minimum punishment of 7 years of imprisonment under any existing law.

Serious offences– such offences for which there is a minimum punishment of 3-7 years of imprisonment.

Petty offences– offences with a maximum punishment of 3 years.

- The 2015 Act provides that if a juvenile between the age of 16-18 years has committed a heinous crime as defined above, he should be tried as an adult. Whether a juvenile was to be tried as an adult or not would be decided by JJB after examining the juvenile’s mental and physical capacities,etc.

- The powers and functioning of Juvenile Justice Board(JJB) and Child Welfare Committees(CWC) were more clearly laid down. This Board was to act as a separate minor court since they are not to be taken to criminal courts. It was meant to be not intimidating but a child-friendly place. The CWCs were empowered to deal with children who needed care and protection. They were to take care of matters relating to care, protection,treatment,rehabilitation and development of the children. Children in need of care and protection could be placed in foster care on orders of CWC.

- Registration of all Child Care Institutions was made mandatory under this Act.

- Central Adoption Resource Authority(CARA) which deals with adoptions in the country was given statutory status under the Act. The Act aimed to create an organised and efficient system to carry out adoption of orphaned, abandoned and surrendered children.

- Special Juvenile Police Units designated for handling minors were to be set up in each state police force.

THE JUVENILE JUSTICE (CARE AND PROTECTION OF CHILDREN) AMENDMENT ACT, 2021

Key features:

- Under the earlier Act, a civil court was the issuing authority of an adoption order. However, after the amendment, this power has been vested with the Distriсt Magistrate( including the Additional District Magistrate) in order to expedite the process and clear the pending cases. Any person aggrieved by such an order may file an appeal before the Divisional Commissioner, within 30 days from the date of passage of such an order.

- Addition of another category to the list of serious offences. It will also include those crimes for which maximum punishment is imprisonment of more than seven years, and minimum punishment is not prescribed or is less than seven years.

- The Act provided that the heinous crimes committed by juveniles would be tried in Children’s court (equivalent to the sessions court) whereas other offences would be tried by a Judicial Magistrate. The amendment provides that all offences under this act will be tried in the Children’s court.

- Under the 2015 Act, a serious offence committed by a juvenile is cognizable(allowing arrest without warrant) and non-bailable. The amendment provides for such offences to be non-cognizable.

- The new amendment lays down the eligibility of the appointment of members of the Child Welfare Committees.

- The powers of the Distriсt Magistrate and Additional District Magistrate have been enhanced to monitor and evaluate the agencies responsible for implementation of the Act.The District Child Protection Unit will now work under the supervision of the DM.The DM has to conduct a capacity and background check of any Child care institution before its registration and suggest changes to the state government. He is now entrusted to independently evaluate Child Welfare Committees, Juvenile Police Units and other registered institutions.

Issues with the Juvenile Justice System:

- Lack of proper implementation: The 2015 Act mandates the setting up one or more Juvenile Justice Boards (JJBs) and Child Welfare Committees (CWCs) in every district. However, it has been found that these bodies have still not been established in many districts. They were found to exist on paper even when they were not functioning. It was noted by The National Legal Services Authority (2019) that only 17 of 35 states/Union Territories (UTs) had all basic structures and bodies required under the Act in place. States such as Assam, Bihar, and Haryana, still did not have CWCs in all districts. The Standing Committee on Human Resource Development (2015) also noted that CWCs and JJBs are dependent on the state or district administration to manage their finances and human resources. Action taken by them was limited and delayed due to lack of infrastructure or specific funds. It recommended greater financial allocation, training and cadre-building for various bodies.

Institutions under the Act (January, 2019)

Institution

|

Number of states/ UTs with the institution

|

District Child Protection Society

|

34

|

Child Welfare Committee

|

27

|

Juvenile Justice Board

|

30

|

Special Juvenile Police Unit

|

34

|

Child Welfare Police Officer

|

32

|

Juvenile Justice Fund

|

25

|

- Child care institutions- CCIs refer to institutions including open shelters and specialized adoption agencies, which provide care and protection to children in need of such services. It has been noted that most of these CCIs fail to provide even basic services expected of them. Moreover, a large percentage of the CCIs still continue to be unregistered and therefore unregulated.

- Delays in adoption- Under the 2015 Act, Central Adoption Resource Authority (CARA) was declared a statutory body in order to promote, regulate and expedite the process of adoptions. However, it was brought to notice by the Madhya Pradesh High court in 2017, that CARA failed to provide timely referrals to children declared legally free for adoption.

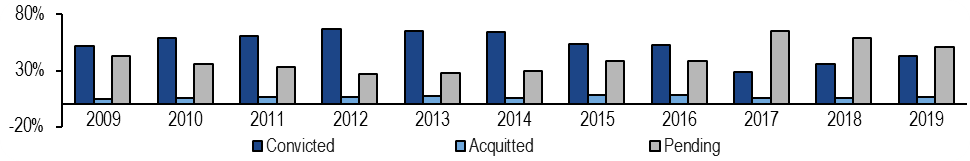

- Pendency of cases- Pendency of cases of juveniles in conflict with law has increased over the years from 43% in 2009 to 51% in 2019. The total number of convictions decreased from 52% in 2009 to 43% in 2019, whereas acquittals remained below 10%.

Status of disposal of cases filed against children in conflict with law

Sources: Crime in India, 2009-2019, National Crime Records Bureau; PRS.

📌Analysis of Bills and Acts

📌 Summary of Reports from Government Agencies

📌 Analysis of Election Manifestos