Abstract

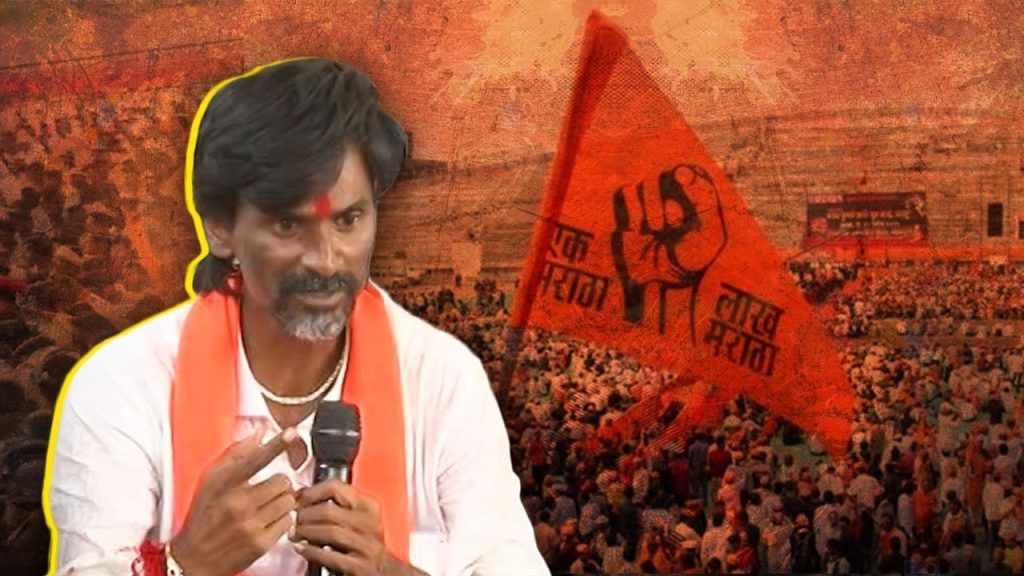

The idea of reservation was introduced to India during the Hunter commission in 1882. It was later inculcated in the Constitution of India, with various provisions safeguarding the rights of the backward classes. The introduction of the Mandal report changed the course of Indian Politics. This led to the introduction of the Kamandal politics to counter the Mandal Politics. This divided the country into Pro and Anti-Reservationists, which led to the political parties using “Identity politics” to win elections. Reservation plays a significant role in the voter turnout in India. This paper focuses on the historical background of reservation, with context to the pre and post independence era, with special mentions of the Mandal Commission Report and the Articles regarding Reservation in the Indian Constitution. It sheds some light on some of the burning reservation issues in India, including the Maratha reservation issue, the Jat agitations, the Gujjar reservation issue, the OBC issue in Uttar Pradesh, and the Patidar Agitations. This paper also gives references to the Women’s reservation bill and the argument surrounding it. It also talks about the role reservation politics play in the voter turnout, and the countering Anti-Reservation protests.

Introduction

The Constitution of India includes various provisions to safeguard the interests of socially, economically and educationally disadvantaged groups. This also ensures their adequate representation in state services. In India, the Reservation is used as an affirmative action strategy, which grants the backward classes opportunities for government job positions, access to educational institutions, and participation in legislative bodies. However, it has sparked controversies in India. These policies have also sparked numerous agitations and protests, reflecting the complex and multifaceted nature of this issue in Indian society. The Politics of Reservation has been time and again used as an electoral strategy. This paper focuses on the historical background of reservation, with focus on various developments like the Mandal report, which shaped Indian Politics thereafter. It further sheds some light on the Reservation related agitations in India, along with its impact on politics.

History of Reservation system in India

Pre-independence era:

In 1882, the idea of caste-based reservation system was first perceived by Shri Jyotirao Phule and Mr. William Hunter. The first notification providing reservation for the welfare of backward people in India was made in 1902, with the announcement of 50% reservation in services in the state of Kolhapur. In 1908, reservation was introduced only in the favor of those communities and castes, who had some part in the British administration. Some provisions were also made in the Morley-Minto reforms of 1909. The actual legal origin of reservation policy began with the Government of India Act in 1919 in India. This Act introduced the communal electorates along with several reforms in Indian Governmental institutions. The Madras presidency introduced a Government order in 1921 providing 44% reservation to non Brahmins – 16% reservation for Muslims, 16% reservation for anglo-christians and 8% reservation for scheduled castes. Later in 1927, when the controversial Simon commission came up to scrutinize the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms, they proposed combining separate electorates and having seats reserved for depressed classes. In order to scrutinize and incorporate these recommendations and reforms in the new constitution, a round table conference was convened in London in 1931, with the presence of several Indian delegates. This conference was chaired by the then British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar appealed for a separate electorate for the depressed classes, however this was opposed by Shri Mahatma Gandhi, who thought this would divide India further. Hence this issue remained unsolved in the conference. Prime Minister Ramsay McDonald gave his award called the “Communal award” in August 1933. This provided for separate representation to be made for Muslims, Sikhs, Indian Christians, Anglo-indians and Scheduled castes. This was supported by Shri Dr. B.R. Ambedkar and opposed by Shri Mahatma Gandhi. The Poona pact was signed to address this issue. This pact brought in a single general electorate for each of the seats of British India and new central legislatures. This pact was inculcated In the Government of India Act of 1935, in which seats were reserved for depressed classes.

Post Independence era:

The Reservation policy gained momentum in the post independence era. This was drafted by the constituent assembly headed by Dr. B. R. Ambedkar. The Supreme Court, in 1951, in the State of Madras v. Smt Champakam Dorairajan, held that the caste based reservation violates the Article 15(1) of the Indian Constitution. In order to invalidate the above judgment, the 1st constitutional amendment was made. This was followed by addition of clause (4) in the article 15. The Kalelkar Commission was established in 1953, to review the situation of the socially and economically backward classes. The Supreme Court later established a 50% cap on reservation in the case of Balaji v. Mysore in 1963. The Mandal commission was established in 1979, to see the condition of socially and educationally backward classes. This commission submitted its report in 1980, and was implemented in 1990. Special 10% reservation for the poor was introduced by the Narasimha Rao Government in 1991. The Parliament under the 77th constitutional amendment added clause (4) (A) in the article 16 of the Indian constitution in 1955. This provided for reservation and promotions to SCs and STs. The Supreme Court in P. A. Inamdar and Ors v. State of Maharashtra and Ors case held that the state cannot make reservations on minority and unaided private colleges, including private professional colleges in 2005. Later that year, the 93rd amendment was brought to ensure the reservation policies.

Click Here To Download The Paper

📌Analysis of Bills and Acts

📌 Summary of Reports from Government Agencies

📌 Analysis of Election Manifestos